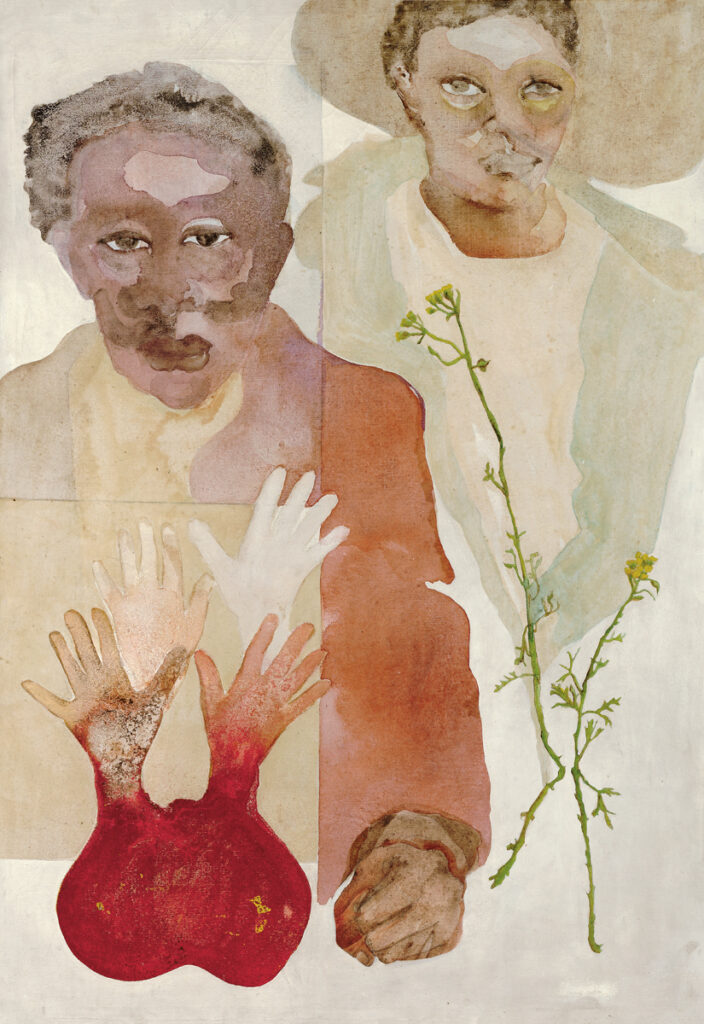

Suzanne Jackson

Love, Peace, and Beauty

Suzanne Jackson: What Is Love celebrates the painter’s groundbreaking artistic vision with more than 80 lyrical paintings and drawings from the 1960s to the present. Here, Jackson talks about her creative upbringing, the evolution of her work, and what it means to have her first major museum retrospective open in San Francisco.

What is the significance of What Is Love, the exhibition’s subtitle?

Suzanne Jackson: Originally, the curator of the exhibition [Jenny Gheith, curator and interim head of painting and sculpture] was thinking of the title from my first publication What I Love (1972), but I am a completely different person now. So many things have happened in the world in the 60-plus years that I have been making art. I’ve lived through so many things. Love is something very broad. I would like people to give it their own interpretation.

You have lived in San Francisco at various points throughout your life, including part of your childhood. What impact has the Bay Area had on you?

SJ: I think of visual moments from the time I was a baby. Going through Golden Gate Park, going to all the monuments, riding the cable cars — I still think it’s the most beautiful city in the United States and in the world, really. As a child, seeing these things and places and making drawings and paintings from them was my first life experience that gave me so much. It’s just a different atmosphere from other cities.

Along with visual art, you have a background in poetry, theater, dance, and costume and stage design. How have these other art forms influenced you?

SJ: I was really influenced by musicals that we’d see on television. I used to perform for my parents. And my mother was a fashion designer.

I spent college dancing, painting, and writing. At San Francisco State, there were poetry readings constantly next to the painting department. We also did the West Coast version of West Side Story with choreographers I’d studied with at Pacific Ballet. I was known more as a dancer than as a painter and I was a little annoyed because I really wanted to be known as a painter. I thought, “Well, maybe I’m just not good enough yet. I’ve got to become a better painter.”

Because people knew I had been a dancer, they associated my figurative works of things floating in space to dance. It was more me attempting to learn how to paint and work with composition in space, but subconsciously things come out. And my early titles would be little pieces of poetry. I do not believe any of the arts are separate. In theater there’s literature, movement, and visual arts, all combined on stage.

How did your art practice evolve from paintings and drawings to hanging, three-dimensional works?

SJ: The retrospective goes through my life, learning how to paint, how to draw. One year, I had a fellowship to make monoprints, which made me very aware of the beauty of some papers that most people would throw away, then discovering what paper could do with acrylic paint and how it could be shaped and formed.

Because the netting from produce bags did not work on my fruit trees — the possums and squirrels ate the fruit anyway — I began using it in my art to suspend acrylic paint. I’m still trying to make pure acrylic paintings that will hold up, as opposed to having canvas or something else as a support. That’s my goal. I have a few paintings I love most because they are structurally very strong. Sometimes the smaller paintings are much more powerful than large ones.

As acrylic paint has developed through the years, the paint and the hues are the same, but the mediums that can be added have improved. Each company is different. One company may make a medium that will not hang, while the medium I use all the time, the strongest, is one I can repair my house with.

“I realized when I was able to suspend the paint in space that I had something that was really my own, that I was not copying or imitating anyone else.”

SFMOMA’s collection includes two of your paintings: El Paradiso (1981–84) and a later hanging acrylic, Hers and His (2018). Can you share more about these works?

SJ: El Paradiso I started in Los Angeles — the city flower is the bird of paradise. The painting traveled with me to San Francisco and I worked on it there. It’s a California painting because it represents the flora and fauna, and all the places I’ve lived in the state. Later I got sick of my early bird and heart paintings because everybody loved them. As a painter, I thought I needed to grow out of that romantic period of my younger life.

Hers and His happened when I found my mother’s “his and hers” pillowcases. My mother was the kind of 1930s wife who controlled everything in the house; every room was decorated the way she wanted. Those quilt pieces in Hers and His were her rejects. I added pom-poms at the bottom, being sort of silly. This was before I was working with the pure acrylic hangings; it was a way of getting there.

Can you say more about ¿What Feeds Us? (2025), the new site-specific installation in the exhibition?

SJ: The commission includes works that hang on the walls and a sculptural centerpiece, which I realized would be too large to get out the door of my studio in Savannah, so we moved it to my studio in Saint Remy, New York, which has huge French doors. It became a very organic piece influenced by that environment of the woods with elements of logs, and plastics that wash up on shores. All of the plastic garbage I’ve overpainted and distressed. One of the things I loved in theater and set design was distressing. I’m good at getting things ugly and dirty looking. It should look as if it’s washed up from the ocean onto this beautiful structure full of moss and wood.

What does this retrospective mean to you?

SJ: It’s big-time. The exhibition is being organized so beautifully. My understanding as a young artist was that you do not receive certain recognition until your work has matured. I realized when I was able to suspend the paint in space that I had something that was really my own, that I was not copying or imitating anyone else. This is the work I have matured into, and it’s being documented and held in time by the most incredible group of humans.

It’s also an honor for my parents, who were some of the pioneers who migrated during World War II to San Francisco. To open in San Francisco is wonderful because it’s where I began seeing aesthetically.

“There’s really only one place in the world where love and peace and beauty are given, and it’s in the arts.”

What’s next for you?

SJ: The wonderful thing about being an artist is that we work for ourselves and no one can stop us. I’ve had examples of people like Betye Saar, who is turning 100 years old next year and still working, and artists like Elizabeth Catlett, June Leaf, and Jacqueline de Jong, who worked till the end, and I’m going to do the same thing.

I am encouraged, influenced, and supported by the work I see by other artists. That is exciting that people are still pushing and giving love to others. There’s really only one place in the world where love and peace and beauty are given, and it’s in the arts.